I am typing out the booklet notes as I cannot comment whatsoever on Weinberg's 8th.

Here's hoping we all enjoy it! I have a premonition it's going to go swimmingly. On to the notes.......

Mieczysław Weinberg was born on 8 December 1919 in Warsaw, where he emerged as a highly regarded pianist. He might well have continued his studies in the United States until the Nazi occupation saw him flee to Minsk (in the course of which his travel documents were inscribed as Moisey Vainberg, by which name he was ‘officially’ known until 1982). During 1939–41 he studied composition with Vasily Zolotaryov, then, soon after the Nazi invasion, he headed further east to Tashkent where he immersed himself in theatrical and operatic projects. There he also wrote his First Symphony, which favourably impressed Shostakovich and resulted in his settling in Moscow in 1943, where he was to remain for the rest of his life. In spite of numerous personal setbacks (his father-in-law, actor Solomon Mikhoels, was executed in 1948 and he himself was briefly imprisoned for alleged Jewish subversion prior to the death of Stalin in 1953), he gradually amassed a reputation as a composer who was championed by many of the leading Soviet singers, instrumentalists and conductors.

Despite several official honours Weinberg’s fortunes declined notably over his final two decades, not least owing to the emergence of a younger generation of composers whose perceived antagonism to the Soviet establishment ensured them much greater coverage in the West, and his death in Moscow on 26 February 1996 went all but unnoticed. Since then, however, his output—which comprises 26 symphonies and seventeen string quartets, along with seven operas, some two dozen song-cycles and a wealth of chamber and instrumental music—has received an increasing number of performances and recordings, and has been held in ever greater regard as a substantial continuation of the Russian symphonic tradition.

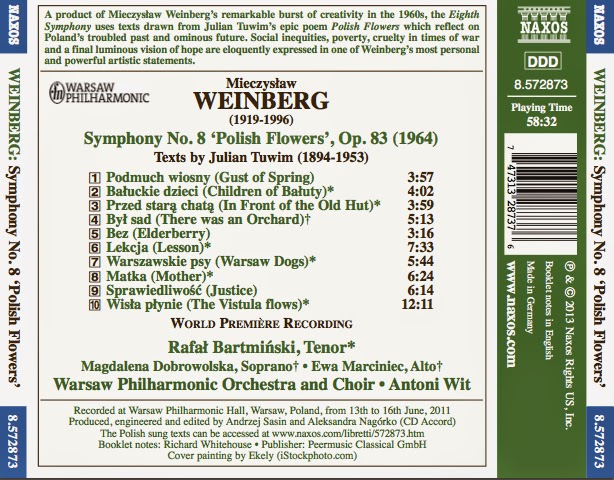

The 1960s was a decade of great productivity for Weinberg and not least in terms of the symphony, with seven written from 1962 to 1970. After the Fifth Symphony, moreover, his largest pieces in the genre were choral, beginning with the Sixth Symphony then continuing with the Eighth and Ninth. Composed in 1964, the Eighth is his first wholly choral symphony, its twelve movements drawing on the epic poem (itself the only completed part of an intended trilogy) Polish Flowers by Julian Tuwim (1894–1953), whose poetry Weinberg set as early as his song-cycle Acacias of 1940. At once a history and a critique of Poland over the period between the two world wars, Tuwim’s verse struck a resonance in Weinberg who, other than a visit to the Warsaw Autumn Festival in 1966, was not to see his native country after having fled the Nazi advance in 1939. The Eighth Symphony, first given in Moscow on 6 March 1966 by Alexander Yurlov with the Russian Academic Choir and the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra, is therefore among his most personal artistic statements.

The first movement, Gust of Spring, sets the tone for the work as a whole with its reflections on Poland’s troubled past and ominous future. It begins pensively with female voices sounding plaintively over tolling lower strings and percussion, the former continuing at length until strings have an elegiac response that is continued by solo clarinet towards the close.

The second movement, Children of Bałuty, evokes the social inequities of pre-war Poland as seen through the industrial landscape of Bałuty, a suburb of Łódź. It commences with lively and rhythmically agile writing for female voices over a pizzicato accompaniment which soon draws in the strings and woodwind. A pause and then the tenor soloist responds in more immediately expressive terms, before elements of both themes are briefly combined prior to the brusque ending.

The third movement, In Front of the Old Hut, surveys the degradation endured by the mass of Polish people in earlier times. It starts with plangent woodwind entries that are joined by solo tenor in an almost Baroque-like texture, offset by discreet gestures on percussion. Strings and muted brass enter before unaccompanied voices bring about a hushed conclusion.

The fourth movement, There was an Orchard, expands on the issue of poverty with its depiction of the squalor common to peasants, gypsies and Jews alike. It begins with a burgeoning of folk-like gestures on woodwind and strings—the chorus entering stealthily, followed by a dialogue for soprano and mezzo soloists from within the chorus. The emotional mood heightens only gradually, with the instrumental component becoming more forceful prior to its sudden curtailment.

The fifth movement, Elderberry, contrasts the hope offered by springtime with the alienation of urban life. It commences with solo tenor accompanied by wistful woodwind gestures over a chord in lower strings. The chorus responds in almost prayerful terms, leading on to the work’s initial climax in which the whole orchestra is also to be heard for the first time.

The sixth movement, Lesson, is a warning to Polish infants of the inequities that they are to encounter. It opens with dance-like music for chorus and orchestra, percussion much in evidence. This tails off to leave the chorus sounding hesitant over fragmentary gestures on woodwind and brass, before the activity resumes on orchestra alone. The chorus then re-emerges at its height, after which calmer yet sombre exchanges between brass and percussion gradually subside into nothingness.

The seventh movement, Warsaw Dogs, equates the cruelties dealt out to dogs with that of the Polish people in time of war. It launches with stark unison chords on piano and percussion, chorus and woodwind replying with similarly forceful writing which builds in intensity until the initial chords are hammered out by full orchestra. An impassioned tenor solo brings a sudden hush, with only fugitive gestures from voices and instruments remaining prior to a powerful orchestral chord.

The eighth movement, Mother, takes the murder of a woman at her son’s grave as emblematic of the atrocities inflicted by the Nazi invaders. It unfolds with an eloquent solo from tenor over static chords—derived from that which ended the preceding movement—on lower (wordless) voices and instruments. At length a solo horn and then upper strings wearily assume the melodic foreground, followed by glacial gestures on celesta and lower woodwind as a rounding off.

The ninth movement, Justice, contrasts the collapse of Nazi rule with a promise of freedom and equality in the wake of the Soviet victory. It starts with starkly dramatic writing for unaccompanied voices in rhythmic unison, with a discreet underpinning from strings and brass at key moments. A more passive section (derived from the 1958 song-cycle Reminiscences) finds the chorus in subdued dialogue with woodwind (derived from the 1958 song-cycle Reminiscences) before a climactic unison gesture from chorus and orchestra.

The tenth movement, The Vistula flows, likens the poet’s verse to the flowers of Poland that each year bring new hope, with the river Vistula as a metaphor for the indestructibility of the Polish spirit. It begins with an expressive solo from the tenor, continued in more ruminative terms by the chorus over a luminous orchestral backdrop. The tenor resumes in more measured terms against an imploring choral response, before the woodwind gestures from the fifth movement reappear prior to the chorus bringing about the work’s main climax in a monumental passage for all the voices and instruments combined. This rapidly dies down to leave fragmentary choral gestures, together with recollections from the very opening of the work, as the plangent sound of upper woodwind brings about a subdued yet tenuously optimistic ending: as if to reflect, in Weinberg’s own words, ‘the deep faith of the poet in the victory of freedom, justice and humanism’.

Weinberg_Symphony_No.8_Tveti_Pol'shi-Tzadik.zip

http://www31.zippyshare.com/v/1flzA5BJ/file.html

8 comments:

Just found your blog tonight. I must say that this recording is fantastic. thank you very much. Great Blog.

Hi E Craig, welcome. I just listened to the whole work for the first time myself and I have to say as usual-Weinberg can do no wrong by me :) Hope you enjoy it here! TZ

Great and beautiful music.

Power and delicacy wonderfully balanced.

Thanks a lot for sharing.

Best wishes

Sergio Pontalti

Great share! Your blog is one the most exciting music blogs/shares out there!

Piterets

Haven't listened to it yet,but thank you so much from Jerusalem.

Hello Sergio, thank you for commenting! Happy you like the symphony, 'power and delicacy' in this particular case (as far as Weinberg is concerned) is achieved; the orchestral forces and mass of voices together make a rather beautiful and convincing argument. TZ

Hey Piterets, it's always nice to hear from you. Thank you again for your kind words, friend. -Have you ever heard of the cellist and composer Okkyung Lee? Her best music has been released on Tzadik. She writes experimental jazz, contemporary classical, noise (in a beautiful, musique concrète fashion) with other ingredients such as Korean folk music.. Thinking about posting ones of her albums. TZ

Hello theblue, nice to hear from you as always my friend. Hope you did enjoy the Weinberg by now! Regards, TZ

Post a Comment