It took me many years to warm up to and have the patience for serious organ music, but I think once you get it, you "get it". The organ provides endless musical possibilities, and one needn't look much further than JS Bach's massive and towering output to hear why. Durufle, Widor, Sowerby, Willan, Jongen, Petr Eben and Samuel Adler also come to mind especially for me. Also I have to say I am not a fan of Phillip Glass (exceptions being his String Quartets and certain 'sections' from a few of his operas) however his organ works (some of which are taken from other compositions) are among my favorites from the entire Organ repertoire. The "Glass Organ Works" disc on Catalyst is imo a real treasure chest of 20th century organ pieces. If people are interested, I wouldn't hesitate to post it.

Hindemith’s three organ sonatas especially are superbly composed and nicely compact. (They have with justification been described as cornerstones of 20th century organ repertoire) The Interludes taken from Hindemith's large and important piano work "Ludus Tonalis" also are especially fine.

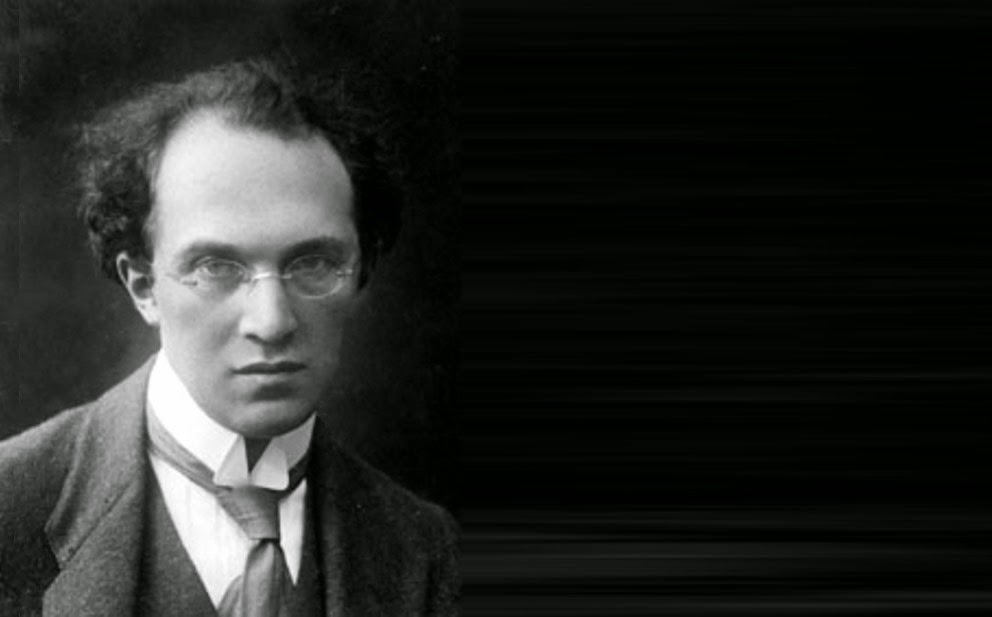

Paul Hindemith was actually no organ music specialist. Despite, or perhaps precisely because of this, he created a body of work that is an integral part of twentieth-century organ literature and is nowadays, after a long period of reserve on the part of many organists, very popular. As mentioned above three Organ Sonatas are among the great works of modern organ literature.

As a musician, Hindemith was an all-rounder. After receiving a comprehensive education from Bernhard Sekles and Arnold Mendelssohn (composition) and from Adolf Rebner (violin), he joined the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra and was its concert master from 1915 to 1923. He played viola in the famous Amar Quartet from 1922 to 1929, made concert appearances as a soloist and conductor worldwide, and was Professor of Music Theory at the Hochschule fur Musik (Academy of Music) in Berlin from 1927 to 1934. The Nazis considered his music to be "degenerate art", so the composer, whom Goebbels had reviled as an "atonal noisemaker", left Nazi Germany, living first in Switzerland, from 1938, and then, from 1940 onwards, in the United States, where he taught at Yale University in New Haven until 1953. That year he returned to Switzerland to teach theory of music at the University of Zurich. With the all-embracing reach of Hindemith’s work and interests as an artist came an engagement with the compositional questions of his day that is reflected in his didactic work Unterweisung im Tonsatz (1937–39; published in English as The Craft of Musical Composition) and his book A Composer’s World (1952, published in his own German translation in 1959 as Komponist in seiner Welt).

Hindemith’s music belongs to the great German tradition of Bach and Max Reger. He thought very highly of the latter, once saying: "Without him, I am unimaginable". A mastery of counterpoint, clarity of form, a bold and emancipated harmonic language that nevertheless adheres to "tonal centers", original and transparent structuring of thematic material, an interest in the individual characters and demands of instruments that is both questing and open to experiment—such are the stylistic elements that make Hindemith’s musical language unmistakable. He approached the organ not as a specialist, but with the wealth of experience he had accumulated as a composer with an overall plan; between 1935 and 1943 he wrote, in quick succession, 22 sonatas for all the main orchestral instruments. His Organ Sonatas are part of this overarching artistic development, and it is this which gives them their individual character and makes them seem new, distinctive and original, even though they build on existing tradition.

Influenced by World War I, in which his father lost his life in 1915 and he himself fought as a soldier in 1917–18, Hindemith found his way to an unsentimental musical style of “Neue Sachlichkeit” ("new objectivity"), turning away from the Romantic pursuit of emotional expression. He became interested in historical performance practice—he himself played the viola d’amore—and was aware of the efforts of the so-called "Orgelbewegung" or organ reform movement to reconstruct period organs and perform Baroque music in an authentic manner. Here too, his lack of specialization was an advantage: he was not wedded to the organ reform movement’s agenda, and he did not limit the organ to its allegedly polyphonic character, instead approaching it with the same openness and curiosity that he brought to every other instrument. And since his musical style exhibited polyphonic and contrapuntal characteristics in any case, he did not need to make any particular song and dance about polyphony in his organ works. Nowhere in his organ music does he employ sacred themes (such as chorale tunes); it is conceived as pure concert music and not as church music. As far as registration is concerned, Hindemith was more open-minded than many organ composers of his day, allowing the use of Orgelwalzen and swell pedals, which made it possible to achieve huge crescendos. In the preface to the Third Organ Sonata he writes: “Those playing organs with a crescendo pedal and swell box are at liberty to use richer colouration and dynamic transitions to raise the dynamic level of the phrase above that which is indicated.” The organ has often been compared to the orchestra. "My new organ? It’s an orchestra!", said Cesar Franck, referring to the possibility of imitating any instrument and achieving powerful combinations of sounds. Hindemith thought differently and wanted transparency of sound, as he wrote in a letter to the organ builder Weigle: "I have a particular conception of the organ. I hate those gigantic organs that sound soft and bloated, I love clear, rational specifications, pure and cleanly articulated voices". Kirsten Sturm therefore consciously takes Hindemith’s clear orchestral sound as her starting point, using a lot of bright registrations that are rich in harmonics. In the First Sonata, for example, particular groups of instruments (strings, woodwind) are assigned to the different themes. The varied colors of the Sandtner organ facilitate her attempts to present Hindemith’s music in a lively rather than in a dry and brittle manner.

The "Zwei Orgelstücke" (Two Organ Pieces), Hindemith's earliest works for the instrument, were composed in 1918 while he was in France doing military service. His diary entry for 11 August reads: "Nothing new. Air raid warning, a few bombs that caused considerable damage. Composed. A piece for organ". The Praeludium is a playful, pianissimo piece with animated semiquaver figures and calm, held pedal notes (to be played using a bright, 4’ stop). The second piece, marked Mäßig schnelle Halbe (moderately fast minims), has no title, probably because it is quite free in form and character. The theme is chromatic and late-Romantic. It returns several times, clad in shimmering harmonic colours and polyphonic variants. The development twice rises to a fortissimo, the first time in F minor, the second time in B major. The two pieces thus constitute a "coherent" pair, beginning quietly and ending in a magnificent burst of sound.

Sonata No. 1 (June 1937) is a free treatment of classic sonata form. The first movement employs three themes: the first (in E flat) is a powerful chordal theme, the second theme (in G) is lyrical and songlike. The third theme, marked Lebhaft (Animated) is dance-like and cheerful in character. There is no separate development section; all the themes are developed right from the outset. The recapitulation begins in A—the greatest distance from the exposition (a tritone). Towards the end, the dance-like third theme is repeated three times whilst being brought gradually to a resting point-Langsamer werden (Becoming slower). The first movement concludes with a certain detachment on a harmonically bold 44-bar-long E flat pedal point, above which the manual parts diverge bitonally to E and B natural, before moving via E flat minor to a final resolution in E flat major. The freeform second movement is quite different in character. It begins with an expressive trio movement with three voices treated contrapuntally. Then detachment and restraint are cast aside in a free fantasia with virtuoso passagework, bold chord sequences and strong dynamic contrasts, which runs the gamut of turbulent emotionality and Expressionistic utterance. The final section, marked Ruhig bewegt (Tranquillo) brings a return to classical balance. A gorgeous solo in a graceful 9/8, which Hindemith specified should be played with bright stops (2’ and 4’), leads to a detached, completely relaxed close, which once again concludes with a pedal point on E flat. There is a bold change of chord at the end from G major to a melancholy E flat minor.

Sonata No. 2 (June/July 1937) is the most chamber music-like of the three sonatas. It is less confessional than the First and has a classically clear form. The first movement begins with a succinct, energetic main theme, from which are derived various playful motifs and themes in the manner of a Baroque concerto. A gloomy C sharp minor episode with triple octaves in the lower register ushers in a brief change of mood, throwing the reprise of the lively and spontaneous main theme that follows into greater relief. The second movement is a very lyrical, song-like piece in a rocking siciliano rhythm, the third movement a spirited fugue full of joie de vivre with a rhythmically striking theme. Interestingly, Hindemith eschews contrapuntal refinements such as stretto or augmentation to conclude the fugue, quite atypically, monodically with a statement of the theme in octaves.

Sonata No. 3 was written in the United States in 1940. It employs three love songs from the Altdeutsches Liederbuch edited by Franz Bohme in 1925 and sets them using all the contrapuntal devices and cantus firmus techniques. The first movement is based on the song Ach Gott, wem soll ich’s klagen, das heimlich Leiden mein (Ah Lord, to whom should I lament my secret suffering), the second on Wach auf, mein Hort (Awake, my love), the third on So wünsch ich ihr (I bid her then …), an old cavalry song whose first verse ends with the words: Ich scheide weit, Gott weiß die Zeit, Wiederkommen bringt Freude (I am going far away, God knows how long for, my return will be joyful). There is undoubtedly an autobiographical background here: Hindemith was waiting in the United States for his wife Gertrud, who was of Jewish descent and had remained in Switzerland when he first emigrated. It was not until September 1940 that she reached New York, having travelled via Lisbon. The painful separation from his wife and memories of the old songs and rich cultural heritage of the German homeland he had had to leave under the ruthless power of the Nazis give the sonata a special expressive depth.

The Eleven Interludes (1942) are recorded here for the first time as independent works. They come from the "Ludus tonalis", a kind of twentieth-century Well-tempered Clavier. In that context, they serve as intermezzos to link the twelve fugues, one for each note of the scale. They represent a colorful sequence of character pieces, with a variety of compositional techniques, tempi and moods: now droll (Nos. 1 and 6 are parodies of military marches), now calm and expressive (No. 2 Pastorale), now virtuosic (like No. 4, a perpetuum mobile with semiquavers throughout). The closing Valse (No. 11)—in reality only the schematic suggestion of a waltz—is magical and sits on the border between dream and reality. In 1981 Joachim Dorfmuller arranged the piano cycle for organ, offering organists additional rewarding works by Hindemith. The version for organ is wholly convincing.

Enjoy!

Paul_Hindemith_Works_For_Organ_Tzadik.zip

http://www14.zippyshare.com/v/jiwauyHz/file.html

.jpg)

.jpg)